Fighting or moving with it?

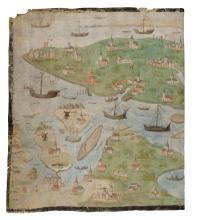

Over the centuries, dealing with water required great decisiveness and enterprise. Between the 11th and 16th centuries, Zeeland and Flanders were hit by countless storm surges. Lost land was re diked if possible, but sometimes shortly afterwards it was swallowed by the sea. Sometimes the inhabitants of the Scheldt estuary were themselves partly to blame for the disasters. Neglected dikes and subsidence due to marsh drainage increased the danger. Some floods were caused by poor drainage due to the silting up of rivers and canals. In addition, the increase of reclaimed land from the twelfth century caused the water to have less space. Many times land was also inundated for military reasons (see story line Contested area).

Protecting?

The first people to settle on the still unimproved land behind the sand barriers and in the Scheldt Valley did so on the higher ground. They are sometimes still recognizable by farms and village centers located higher in the landscape. In Roman times, people built dikes to protect themselves from the water. From the tenth century on, relatively densely populated areas in the salt marshes were also protected with dikes and open creeks were dammed up. As the population increased, it became necessary to protect larger areas.

Kolk lakes and creeks

After floods, welen and creeks remained as "scars" in the landscape. When a dike was breached, a round and deep sinkhole (weel or wiel) was created, around which a new dike was often built. Many creeks in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen and Meetjesland are also remnants of floods, including military inundations. Other creeks are a remnant of original tidal creeks.

Sigma Plan

From the end of the nineteenth century, the level of high water in the Scheldt increased more strongly, partly due to large-scale reclamation and the construction of the Kreekrakdam, which closed the connection between the Eastern and Western Scheldt. To deal with floods, "pot polders" were constructed along the Durme in 1930, also part of the Sigma Plan.

Delta Works

The 1953 flood disaster ushered in the Delta Works. A technical tour de force that, due to the decades it took to complete, itself became the reflection of changing technical and ecological insights. Dikes were raised to the height of the Delta, dams closed off estuaries and the Eastern Scheldt was given a barrier that only had to be closed during storm surges.

Moving?

The Scheldt estuary remains in constant flux. At this time, global warming and sea level rise require new solutions. Lessons from the past and natural processes can help us with this (see also storyline Climate Living Lab).

Discover and experience

The 1953 flood disaster is the subject of the Flood Museum in Ouwerkerk. The Plompe Toren of drowned Koudekerke on the south coast of Schouwen is an iconic landmark. The sea dike at Westkapelle is considered a hydraulic icon. On the south coast of Schouwen and the north coast of Noord-Beveland, inlagen are stringing together. The Zak van Zuid-Beveland is dotted with kolk lakes. An illustrative combination of an elevated village center and farms can be found in the village of Kloetinge and the nearby farmstead Tervaeten. In Bornem, remnants of the Nethof farmstead and the Pastoor Huveneersheuvel recall the medieval settlement of Nattenhaasdonk. Hildernisse, at the foot of the Brabant Escarpment, is the last flood farm in the Netherlands, although it no longer serves as such due to construction of the Markiezaatskade. The Eastern Scheldt barrier can be visited via Deltapark Neeltje Jans. The waterfalls of Kruibeke, part of the Sigma Plan, are a tourist attraction at high tide. Polders throughout the area house numerous locks and other hydraulic works.